By Thomas Albers

Adolescence and young adulthood are critical phases in human development. Young people have to face physical, psychological, intellectual, social and emotional challenges, such as searching for self-identity, achieving independence and autonomy, setting personal goals and making plans, exploring new roles, acquiring and expressing personal values and ethics. Supporting young people to become self-determined in these challenges is an important developmental task of the youth setting. This article takes a closer look at processes of motivation and self-determination and will explore some ways of supporting young people in their journey towards self-determination in these critical life phases.

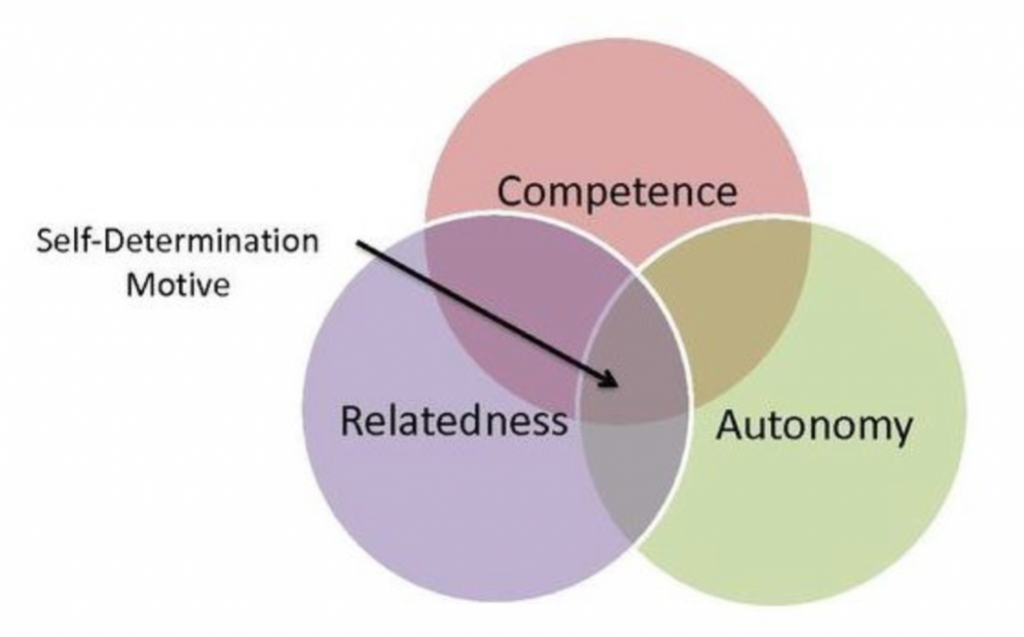

One of the most influential theories on well-being, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), considers human beings as active organisms focused on growth and social integration [1]. The SDT defines three basic psychological human needs as key ingredients for well-being; the need for autonomy, competence and relatedness. The need for autonomy refers to the desire to being able to make one’s own decision about experiences and behaviours, and to take on activities that are in line with one’s own integrated sense of self. It is about experiencing the freedom to decide one’s own path. Feeling competent and able to use capacities leads to having a sense of mastery and confidence to take on challenges. The need for relatedness is about developing relationships, having a sense of belonging, being able to receive and give love and care and feeling accepted. Relatedness is one of the most fundamental human needs, and a pillar of our societies and youth settings.

According to the SDT, fulfilling these basic needs is an essential condition to being able to experience personal growth, mental health and well-being. The youth setting plays an essential role in this process. A youth setting that provides an environment that supports young people to fulfil these needs equally provides the basic ingredients for personal growth, optimal functioning, well-being and developing socially engaged citizens. In general, the fulfilment of all three basic human needs is considered necessary and essential to vital, healthy human functioning, regardless of culture or stage of development. Usually, the unique expression of these three basic needs differs from person to person as each individual belongs to different (sub)cultures, with their own set of values and needs. Satisfying the need for autonomy, for example, will differ according to each individual and their culture. However, despite the differences in expression, the three basic needs have been found to be transculturally important.

Motivation and self-determination

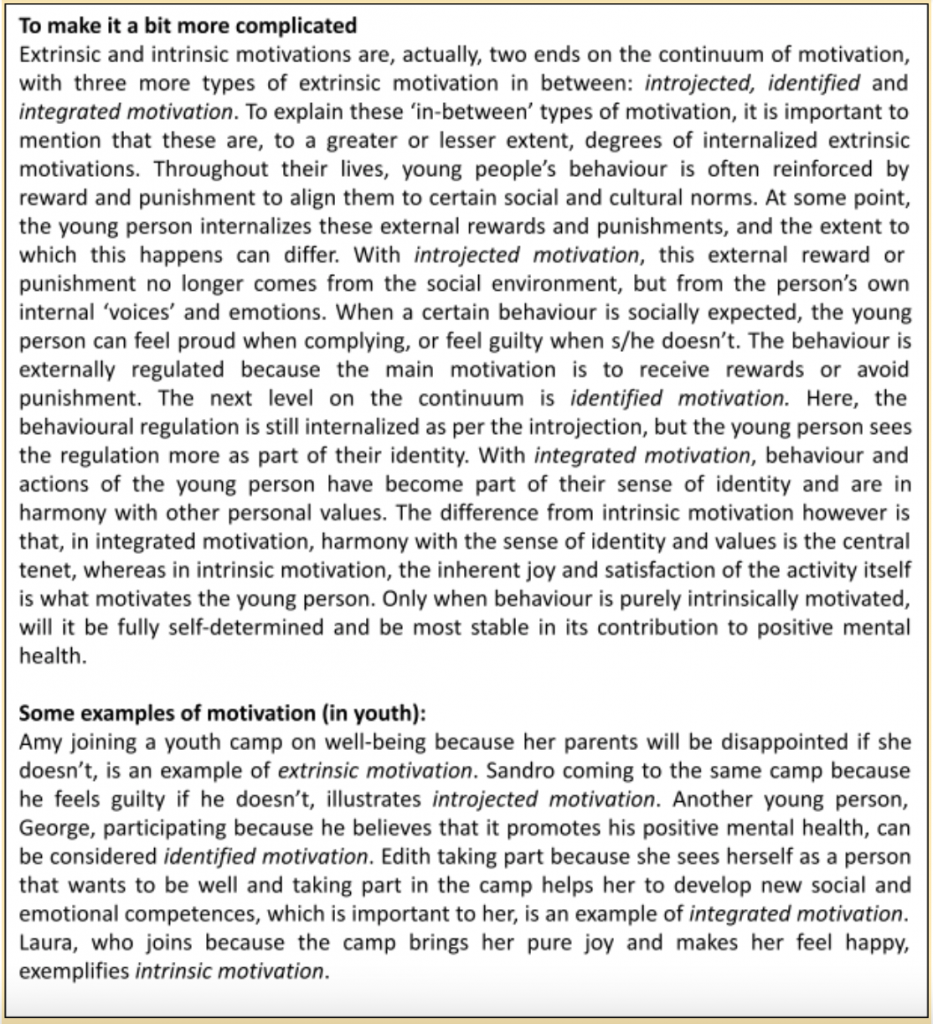

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) describes that the quality of fulfilment of these three basic psychological needs is highly related to the processes of motivation (see figure 1). There are different kinds of motivation, and each motivation has a different degree self-determination. Being self-determined means that one’s behaviour is based on one’s own will, resulting from intentional, conscious choices and decisions. Self-determined behaviour is thus intrinsically motivated; the motivation comes ‘from within’. An activity is intrinsically motivating when the reward is in the activity itself. When young people take part in an interesting, new or challenging activity the reward is often the activity itself, hence intrinsically motivating. An activity can only be intrinsically motivating when we do it out of free will (autonomy), feel competent enough to carry the activity out or able to learn the new competences (competence) and when the activity doesn’t limit our sense of connection to others (relatedness).

Extrinsic motivation on the other hand, is focused on receiving external rewards such as money, status, power, compliments or social recognition. Avoiding punishment, social pressure or feelings of fear and shame are also driving forces in the process of external motivation. Offering these external rewards to young people is limiting their sense of intrinsic motivation. Behaviour that is intrinsically motivated is more sustainable and leads to more positive mental health than extrinsically motivated behaviour, and thus favourable.

Youth work as the road to self-determination

Developing self-determination in young people has many benefits. It enables them to become agents in their own life development and to make independent choices. More specifically, a well-developed level of self-determination has shown to play a vital role in several domains of positive mental health, including beneficial effects on general life satisfaction later in life [2], promote physical exercise, increase physical health [3] and prevent occupational and learner’s burn-out [4]. These are just a few examples of the benefits of being intrinsically motivated and self-determined in behaviour.

In general, youth workers will have young people with many different types of motivation attending youth projects. It is always important to take into consideration and respect their actual and unique situation as it is. Young people’s motivation is a consequence of their past and not showing intrinsically motivated behaviour does not mean they are not doing well. Indeed, self-determined behaviour has just as many benefits and the good thing is that young people have the natural tendency and need for personal growth [1].

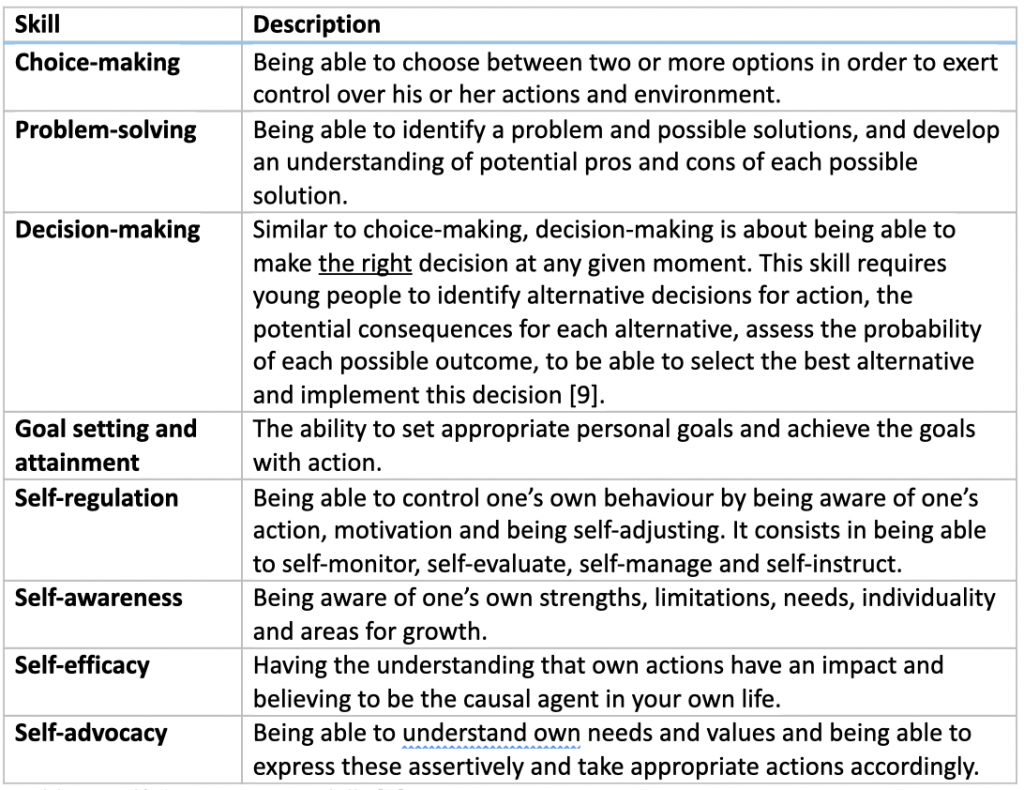

Self-determination of young people is fostered in many ways, including youth work, which is aimed at empowering, engaging and connecting young people. A young person that is self-determined is able to think and act autonomously, feels competent and connected to other people. There are several ways in which the youth setting and the youth worker can contribute to the development of self-determined behaviour of young people. One of them is through fostering the development of self-determination competences (1), such as self-regulation, decision-making and action planning, which have shown to help youngsters become more autonomous, increase their sense of control over personal development and learn to evaluate and set personal goals [5].

This is also true for young people with (severe) disabilities, often and unjustly thought to lack the skills to exert control over their lives [6]. While it may be true that these young people have certain limitations in terms of opportunities, encouraging them to express preferences and promoting self-advocacy is an effective way to increase their sense of agency over their own lives. Promoting self-determination is an important function of youth work (2) and can be done both in a taught and caught manner (3). When there is a designed learning experience that teaches young people the so-called self-determination skills [8] (see table 1), this is considered a taught practice. When, on the other hand, the learning environment itself provides an opportunity to learn these skills, e.g. when the youth organization promotes an active involvement of young people in decision-making, this is considered a caught practice.

To develop effective youth programs (4) aimed at increasing self-determination and, consequently, positive mental health, the self-determination skills [8] in table 1 below should be taken into consideration at planning level. These skills are measurable and most effectively developed through regular practice.

In conclusion, for the youth setting, fulfilling the three basic human psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness and competences) through youth programs is an effective way of promoting intrinsic motivation and well-being. The self-determination skills, as part of the social and emotional competences, can be specifically targeted to support the development of self-determination in young people as an important quality.

Footnotes

(1) Most of these competences are also included in the list of social and emotional competences as defined in the framework on Positive Mental Health, as developed for this project [7]

(2) See Youth Work Function 3 of the Council of Europe’s Youth work competence model. https://www.coe.int/en/web/youth-portfolio/youth-work-competence

(3) See [7], pages 46-49 for more information about these two ways of competence learning.

(4) See the Youth worker’s manual developed for this Erasmus+ project for more guidelines on high quality projects on the promotion of positive mental health and self-determination.

References

[1] Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self‐determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well‐being. American Psychologist, 55, 68‐78.

[2] Lachapelle, Y., Wehmeyer, M.L., Haelewyck, M.C., Courbois, Y., Keith, K.D., Schalock, R., Verdugo, M.A., & Walsh, P.N. (2005). The relationship between quality of life and self- determination: An international study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 740-744

[3] Silva, MN., Vieira, PN., Coutinho, SR., Minderico, CS., Matos, MG., Sardinha, LB., & Teixeira, PJ. (2010). Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized controlled trial in women. Journal of Behavior & Medicine, 33, 110-122.

[4] Fernet, C., Guay, F., & Senecal, C. (2004). Adjusting to job demands: The role of work self-determination and job control in predicting burnout. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 39–56.

[5] Eisenman, L.Y. (2007). Self-determination interventions: building a foundation for school completion. Remedial and Special Education. 28, 2–8.

[6] Wehmeyer, M.L. (2005). Self-Determination and Individuals With Significant Disabilities: Examining Meanings and Misinterpretations. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30, 113-120.

[7] Kuosmanen, T., Dowling, K. and Barry, M.M., (2020). A Framework for Promoting Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing in the European Youth Sector. A report produced as part of the Erasmus+ Project: Promoting positive mental health in the European Youth sector. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion Research, National University of Ireland Galway. www.nuigalway.ie/hpr

[8] Wehmeyer, M. L., Agran, M., & Hughes, C. (1998). Teaching self-determination to students with disabilities: Basic skills for successful transition. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

[9] Wehmeyer, M.L. (2007). Promoting self-determination in students with developmental disabilities. New York, NY: Guildford Press.