By Angelica Paci

REFLECTION AS A KEY ELEMENT FOR PROCESSING THE EXPERIENCE

Every day, young people face life’s experiences, some pleasant and some not so. These experiences can be opportunities for personal development and learning when young people are equipped with the competences to process them in a fruitful and positive way. However, even though experiences are the basis of one’s learning, they are not necessarily always constructive or educative. According to Dewey, there are both educative and “mis-educative” experiences. A mis-educative experience is one that “arrests or distorts growth” and leads to “routine action,” thus “narrowing the field of further experience,” and limiting the “meaning-horizon”(1). Routine actions suggest that one acts without an awareness of the effect of one’s actions on the environment, including others and self. Routine actions turn into habits that dominate us, rather than us having control over them. We thus become unaware of the impact the environment might have on us, and the cycle of growth that results from this two-way interaction is halted.

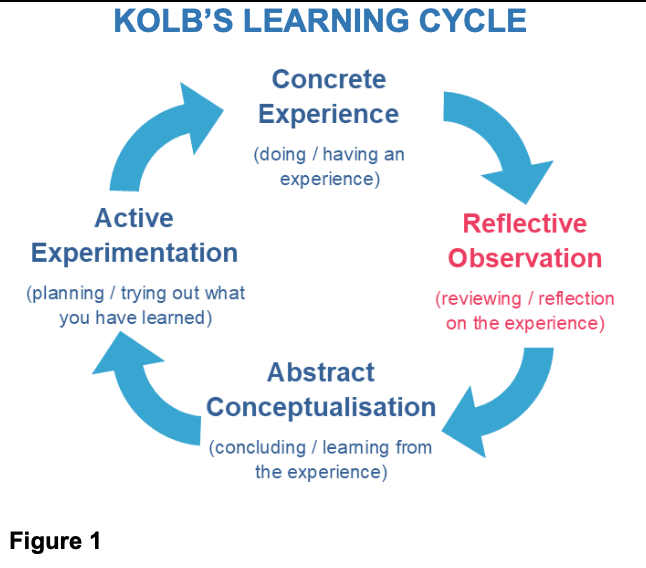

What can support young people to transform an experience into grounded awareness? How can an experience be processed in a way that allows learning more about themselves, others and the context they interrelate in? If we look at Kolb’s learning cycle (2) (figure 1), what turns experience into experiential learning is the reflection process, as it gives time to look at what one sees, feels and thinks after the event has happened. Reflection is an introspective act in which the learner, individually or in a group setting, integrates the new experience with previous ones, making sense of what happened.

Supporting young people in developing a reflective attitude, nurturing what Howard Gardner defined as intra and interpersonal intelligences (3), is, therefore, of vital importance for deepening their awareness about themselves, others and the context they are in. Awareness is a powerful tool to deal with the changes and challenges of everyday life. J. Dewey stated that the main function of reflection is to make meaning and to formulate “relationships and continuities”(4) with the elements of an experience – the links between the experience and prior experiences, between the experience and one’s knowledge, and between that knowledge and the knowledge of other individuals.

Most of the time, many of our thoughts and feelings go unobserved, leading to repetitive, negative patterns in our lives. Developing the ability to slow down, observe and reflect is crucial for gaining understanding, transforming actions and finding forward momentum in life and relationships. The more practiced and capable one is at reflecting on thoughts, feelings, sensations and interactions, the better one is at transforming actions and improving relationships. Reflective practice is empowering and, over time, allows one to become skilful in making informed judgements and more accurate decisions (Robins et al. 2003). We are a learning species and our survival depends on our ability to adapt, not only in the reactive sense of fitting into the physical and social worlds, but also in the proactive sense of creating and shaping those worlds.

REFLECTION AS A HOLISTIC PROCESS

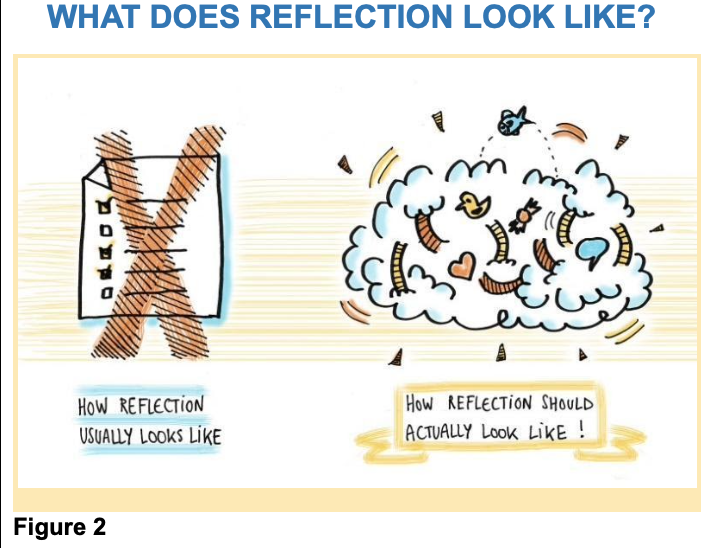

Reflection is very often equated to the evaluation of a certain situation, experience, assignment or process and is used in educational contexts as a means to promote learning. This is, of course, very useful, as it gives the opportunity to look at facts and analyse them in order to check what is working and what is needed, with the aim of improving performance or knowledge. In this case, the focus is mostly on integrating previous knowledge and experiences into new ones, with the purpose of acquiring new skills. This way of looking at reflection gives only a partial idea of the enormous potential embedded in this process, including its applicability. Reflection is, in fact, much more than just a logical cause-and-effect process, as it is subjective and is concerned with feelings and beliefs. Reflection is a resource that can be used in any life context and situation, such as family, group of friends/peers, work, etc. It allows young people to get in touch with themselves and reveal complex thoughts and attitudes. Reflection can include evaluation as part of the process, but goes much deeper, taking different perspectives into account and looking at underlying reasons. Reflection is intended to explore subtle inner and relational processes, with the purpose of revealing causes and personal triggers. When reflection is promoted as a regular practice, either during a planned non-formal activity or in informal contexts, it supports young people facing more complex or uncertain events and behaviours to “dig deeper” and uncover explanations, and possibly solutions, that are not obvious. Dewey claims that the process of reflection moves the learner from a disturbing state of perplexity or ”disequilibrium” to a harmonious state of settledness or “equilibrium”(5). Perplexity is generated when the meaning of the experience has not been fully recognised nor assessed yet. It is a yearning for balance that, in turn, drives the learner to do something to resolve it, thus starting the process of inquiry or reflection(6).

Reflection is therefore no longer conceived as a mere evaluation or logic process of cause-and-effect, but rather as a holistic process of discovery and deep insight. It is a process in which individuals connect body and mind to become more aware of who they are, what they feel, what they think and how they relate to others and the context they are in. “Therefore, reflection is usually indicated by some kind of emotional intensity in which learners demonstrate the connection between themselves and that-which-is-at-stake (the actual topic of reflection). This intensity can sometimes be expressed only in their non-verbal body language. As thinking involves more logic and rationality, this emotional intensity is usually missing.”

FACILITATING REFLECTION

Facilitating reflection is one of the key competences in youth work and one of the most empowering processes that young people can experience. It’s about questioning what is at stake by asking young people when and where things happened, who was there, what did people do, what the outcome of the situation was and what they wanted to happen. It continues with exploring their feelings before, during and after the experience, so that they become aware of what made them feel good (perhaps making them want to feel the same way in other experiences) and what made them feel bad (perhaps making them not wanting to feel the same way in other experiences). Looking into bodily sensations and emotions helps young people to identify underlying needs and wishes, and meeting those needs and wishes helps them create fulfilment. In fact, feelings are spontaneous and emotional responses to what is being experienced and provide essential information about what is actually going on. A warm feeling on the face might mean one is embarrassed, butterflies in the tummy can mean one is nervous or excited and clenched teeth might signify one is angry. Being aware of physical signals allows young people to better identify how they are feeling, and by engaging with how they are feeling, to gain an insight into what they like, what makes them feel anxious, uncomfortable or angry, what makes them feel satisfied or joyful.

As natural progression of those insights, young people can investigate what made things go well and what didn’t in terms of behaviour and attitudes, in order to draw the “lesson” the experience provides, or to better to integrate the learning for themselves. “In action” reflection questions would be “what didn’t I do that I could have done?” and “what could I do that I haven’t done yet?”. Schön was the first to talk about reflection-in-action, claiming that in this process “the practitioner allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in a situation which he finds uncertain or unique. He reflects on the phenomenon before him, and on the prior understandings which have been implicit in his behaviour. He carries out an experiment which serves to generate both a new understanding of the phenomenon and a change in the situation”(7).

All this new learning about themselves, others and their context allows young people to think of possible little steps they can take in order for change to happen. Scientific research(8) suggests that children who are better at reflection are also more successful in all competences in the cognitive domain. Questioning is indeed an important tool to direct the reflective attention of young people, working like a torch in the night, shedding light over what is not processed at a conscious level. Is there a correct sequence or a right question to ask? Questions are shaped in relation to what is happening in the here and now, taking into account the learning context as well as the purpose of the learning experience itself. To build a “reflective space”(9), questioning should be driven by a genuine interest about the learner(s), with an attitude of non-judgmental curiosity with regards to how people see, think and feel about what is at stake. Answers can convey important information for a new question, creating a process of reflection that can lead people to start a dialog with their internal and external ‘companions’ by allowing some distance from their initial thoughts and feelings. In doing so, people will naturally start building the space to reflect within (both individually and collectively), where a co-created dialogue can happen and where silence and “not knowing” are valued. According to Kessels, this not-knowing helps learners to progressively unfold a good quality dialogue with themselves, constructing ‘poetic arguments’ that are quite different from ‘logical reasons’. Reflection is, in fact, a process where part of the information is elaborated unconsciously. Tom Luken claims that “the conscious works serial whereas the unconscious brain works with parallel processes. The conscious brain should necessarily limit itself to a few aspects, whereby there is always a certain arbitrariness. […] Conscious thinking is inclined to use logic, also for questions, paradoxes and dilemmas that can’t be answered with logical thinking. One of the consequences is that in order to get to a solution, inconsistent information gets ‘pushed away’, whereby the eventual decision is based on a distorted representation [of reality].”(10)

Reflection is more effective when it’s conceived as part of a learner-centred approach, as what is being elaborated by the individual is retained in a more authentic and personalized way. The learning comes out of the learners’ frames-of-reference, which determine how they perceive themselves, others and/or the world(s) they live in. This allows young people to take ownership of content, to determine what is useful or relevant to them and build the cognitive connections to allow the learning to be retained.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICES

Reflective practice is the process of making meaning from experience and transforms insights into practical strategies for personal growth. It implies listening, observing and paying attention to oneself, others and context, noticing patterns and facing one’s assumptions, with the purpose of changing the way one looks at things. Reflective practice is a way of recognising and expressing what one is learning in the present moment.

It needs to be captured and represented in different forms (verbal, written, pictorial, sculptural, etc), as learning from experience comes from the process of representing the reflection itself.

Reflective practices are an essential part of developing a healthy habit of reflecting on what happens either at personal or community levels. At a deeper stage, they strongly contribute to the development of young people’s capacity to identify and regulate emotions, respond to challenges, cope with stress, establish healthy relationships, make timely decisions and build new skills. Young people, as well as adults supporting them, can benefit from making use of reflective practices, as in doing so they increase their self awareness, nurture their emotional intelligence and their capacity for emotional regulation.

Reflective practices contribute to the development of young peoples’ leadership, allowing them to:

- build the capacity of making decisions that show a systemic awareness;

- become more able to motivate themselves, to influence others and to be an inspiration for their peers;

- develop the capacity to generate innovation through open questioning and attending to the answers with open mindedness;

- become able to be compassionate to self and others;

- inspire trust through demonstrating trustworthiness.

REFLECTION AS A WAY TO INCREASE AWARENESS

“Reflection is a multi-layered process of identifying, clarifying, exploring that which is-at-stake. It’s a process in which one goes deeper, making connections and meaning, gaining insights between different meaningful ‘events’ (in the broadest possible sense, both internal and external to the reflecting person). As such it leads one to greater awareness”(11) and supports young people, as well as adults, to become more conscious about their relationship with themselves and/or the outer world. The World Health Organisation defines wellbeing as “the state in which individuals realise their own abilities” in order to express their full potential and make a concrete contribution in their community. This means that, first of all, they need to become aware of what their strengths are and understand their own values, beliefs, personal preferences, needs, tendencies, habits and everything else that makes them the unique individual that they are. By becoming self-aware and understanding strengths and limitations, new opportunities open up that just aren’t available otherwise. When young people have a better understanding of themselves, they are able to experience themselves as unique and separate individuals. They become more authentic and tend to have more honest and genuine relationships, as others will be attracted to who they really are. They are empowered and more able to make changes and build on their areas of strength.

THE POWER OF SELF-AWARENESS

Self-awareness has the potential to enhance every experience young people have, as it’s a tool and a practice that can be used anywhere, anytime, to ground oneself in the moment, realistically see oneself and the situation, and help them make good choices.

Research shows that self-awareness is directly related to emotional intelligence, and making it easier to identify what one’s stressors are and use this information to build effective coping mechanisms. Goleman claims that good emotional and social competences give the child the possibility to be effective and to use their cognitive capabilities, while children who do not regulate their emotions remain focused on themselves and not are capable of learning or thinking. Self-awareness as seen by practitioners and researchers is both a primary means of alleviating psychological distress and the path of self-development for psychologically healthy individuals. Fenigstein et al. wrote that “increased awareness of the self is both a tool and a goal.”(12). Being self-aware also means acknowledging that one is not one’s thoughts but the entity observing the thoughts, which gives a great sense of freedom.

To conclude, reflection allows for greater self awareness about one’s unique strengths and limitations, for better being equipped to face challenges, solve problems, make decisions, and predict the outcomes of those decisions. Furthermore, this process helps to analyse the differences and similarities between individuals, with the further benefit of developing interpersonal relationships and of being able to direct one’s communication towards the needs of the others.

References:

(1) Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Collier Books, Macmillan

(2) Kolb, D. (1994) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Engelwoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice–Hall.

(3) Gardner H. (1983) Frames of mind. The Theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books

(4) Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. (Original work published 1910)

(5) Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

(6) Jakube Aurelija, Jasiene Ginte,Taylor Mark, Vandenbussche Bert (eds), Holding the space. Facilitating reflection and inner readiness for learning. Erasmus+ project REFLECT 2014-2015 publication.

(7) Schön, Donald. 1983 The Reflective Practitioner, Basic Books Inc.

(8) Milica Tošić-Radev et all (2016). Capacity For Reflection As A Predictor Of Children’s Readiness For Elementary School. Conference Paper of the 7th International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology.

(9) Ringer, Martin. (2008). Group Action: the dynamics of groups in therapeutic, educational and corporate settings. London: Jessica Kingsley

(10) Luken, Tom. (2010). Problemen met reflecteren. De risicos van reflectie nader bezien. In Luken, Tom & Reynaert, W. (2010) Puzzelstukjes voor een nieuw paradigma? Aardverschuiving in loopbaandenken. Eindhoven-Tilburg: Lectoraat Career Development Fontys Hogeschool HRM en Psychologie

(11) Jakube Aurelija, Jasiene Ginte,Taylor Mark, Vandenbussche Bert (eds), Holding the space. Facilitating reflection and inner readiness for learning. Erasmus+ project REFLECT 2014-2015 publication.

(12) Fenigstein A., Scheier M. F., Buss A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Counselling and Clinical Psychology.

Image credits:

For figure 1 source is https://www.pugetsound.edu/academics/experiential/create-experiential-learning-opportunities/available-resources/creating-critical-reflection-assignments/design-models/kolbs-learning-cycle/

For figure 2-4 Torben Grocholi for the Erasmus+ project REFLECT

For figure 5 source is https://www.worldpulse.com/community/users/gitajayakumar/posts/62911